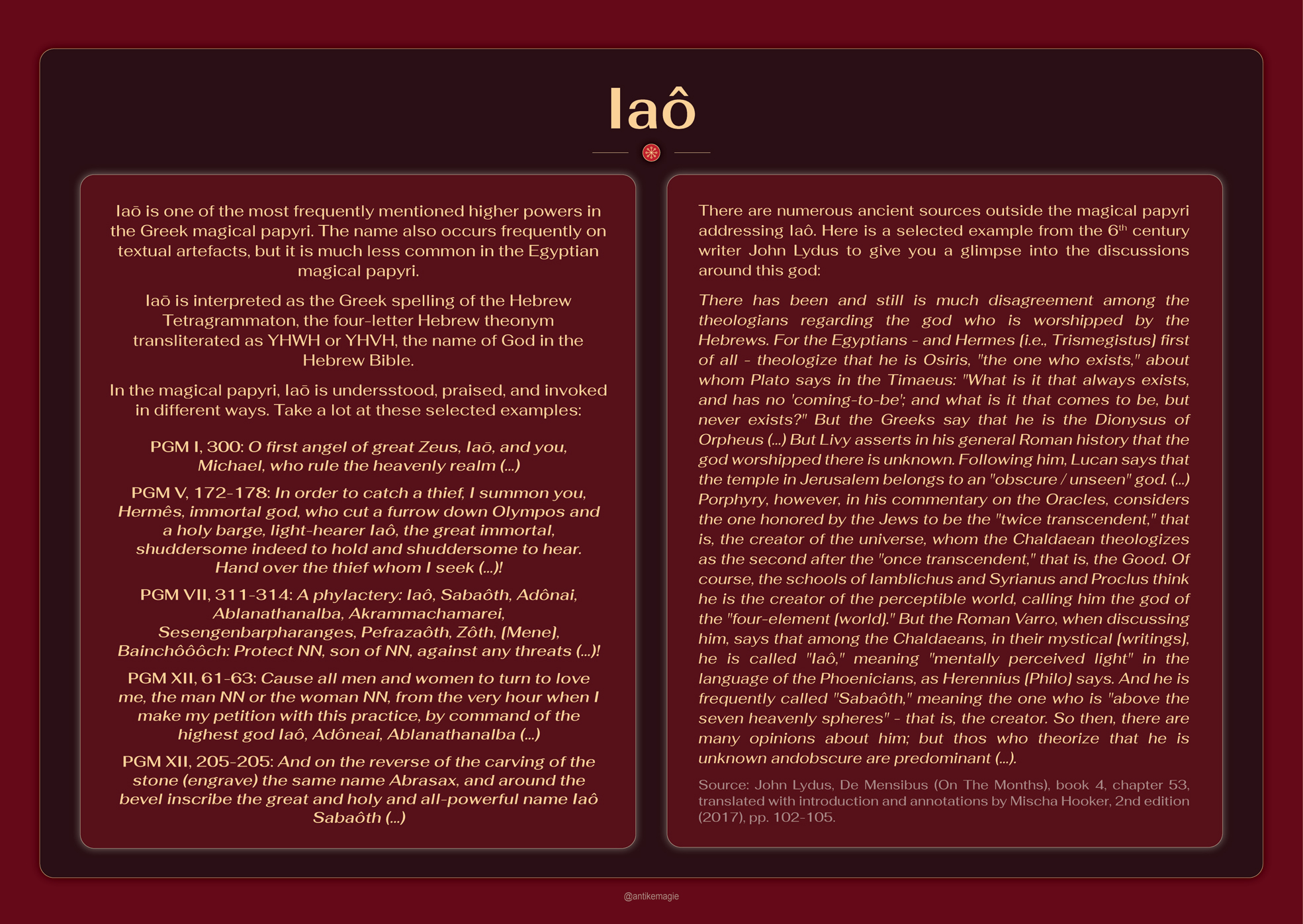

Iaō is one of the most frequently mentioned higher powers in the Greek magical papyri. The name also occurs frequently on textual artefacts, but it is much less common in the Egyptian magical papyri.

Iaō is interpreted as the Greek spelling of the Hebrew Tetragrammaton, the four-letter Hebrew theonym transliterated as YHWH or YHVH, the name of God in the Hebrew Bible.

In the magical papyri, Iaō is undersstood, praised, and invoked in different ways. Take a lot at these selected examples:

PGM I, 300: O first angel of great Zeus, Iaō, and you, Michael, who rule the heavenly realm (…)

PGM V, 172-178: In order to catch a thief, I summon you, Hermês, immortal god, who cut a furrow down Olympos and a holy barge, light-hearer Iaô, the great immortal, shuddersome indeed to hold and shuddersome to hear. Hand over the thief whom I seek (…)!

PGM VII, 311-314: A phylactery: Iaô, Sabaôth, Adônai, Ablanathanalba, Akrammachamarei, Sesengenbarpharanges, Pefrazaôth, Zôth, [Mene], Bainchôôôch: Protect NN, son of NN, against any threats (…)!

PGM XII, 61-63: Cause all men and women to turn to love me, the man NN or the woman NN, from the very hour when I make my petition with this practice, by command of the highest god Iaô, Adôneai, Ablanathanalba (…)

PGM XII, 205-205: And on the reverse of the carving of the stone (engrave) the same name Abrasax, and around the bevel inscribe the great and holy and all-powerful name Iaô Sabaôth (…)

There are numerous ancient sources outside the magical papyri addressing Iaô. Here is a selected example from the 6th century writer John Lydus to give you a glimpse into the discussions around this god:

“There has been and still is much disagreement among the theologians regarding the god who is worshipped by the Hebrews. For the Egyptians – and Hermes [i.e., Trismegistus] first of all – theologize that he is Osiris, “the one who exists,” about whom Plato says in the Timaeus: “What is it that always exists, and has no ‘coming-to-be’; and what is it that comes to be, but never exists?” But the Greeks say that he is the Dionysus of Orpheus (…) But Livy asserts in his general Roman history that the god worshipped there is unknown. Following him, Lucan says that the temple in Jerusalem belongs to an “obscure / unseen” god. (…) Porphyry, however, in his commentary on the Oracles, considers the one honored by the Jews to be the “twice transcendent,” that is, the creator of the universe, whom the Chaldaean theologizes as the second after the “once transcendent,” that is, the Good. Of course, the schools of Iamblichus and Syrianus and Proclus think he is the creator of the perceptible world, calling him the god of the “four-element [world].” But the Roman Varro, when discussing him, says that among the Chaldaeans, in their mystical [writings], he is called “Iaô,” meaning “mentally perceived light” in the language of the Phoenicians, as Herennius [Philo] says. And he is frequently called “Sabaôth,” meaning the one who is “above the seven heavenly spheres” – that is, the creator. So then, there are many opinions about him; but thos who theorize that he is unknown andobscure are predominant (…).”

Source: John Lydus, De Mensibus (On The Months), book 4, chapter 53, translated with introduction and annotations by Mischa Hooker, 2nd edition (2017), pp. 102-105.

Become a patron for more infographics, research and videos: https://www.patreon.com/ancientmagic